Post Views: 11

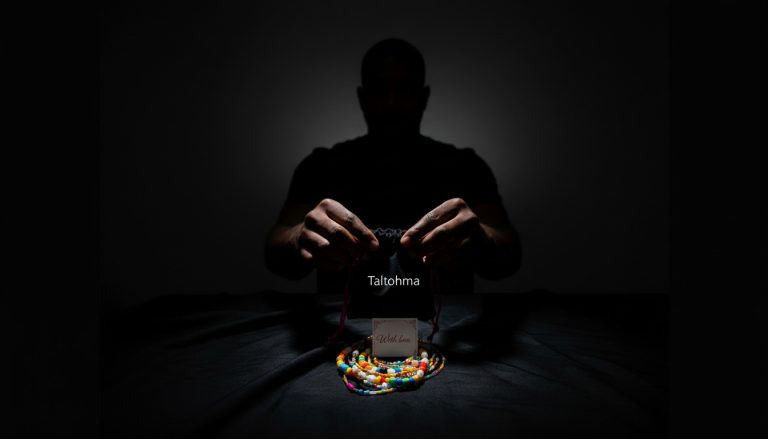

TOHMA: When Love Buys You Beads; The Intimate Meaning Behind the Gift

In Ghanaian slang, when a loved one especially your husband buys you waist beads, it’s called Tohma. And trust me, Tohma isn’t just a name; it’s a feeling, a whole love story rolled into a strand of glass and thread.

When I first heard the phrase, I laughed out loud. Leave it to us Ghanaians to turn romance into cultural poetry. But over the years, as women have come into my studio to buy or collect their waist beads, I’ve realized that Tohma captures something profound the meeting point of love, culture, and quiet seduction.

Now let me tell you a story. It’s been almost four years since one of my VIP clients placed an order and not a small one either. Her beads were worth over $400, and they sit in one of our largest Tohma pots right here in the studio. Fully paid for. Not a cedi left outstanding. But guess what? She still hasn’t collected them.

You’d think maybe she travelled, lost interest, or had a change of heart. But no. Her reason is far more intriguing. She had just given birth when she placed the order. Her husband, who was overseas at the time, had paid for them as a surprise. Sweet, right? He clearly missed his wife. But my client? Oh, she was terrified.

Her reason? “Vera,” she said, “I can’t wear them yet. I just finished nursing. My husband is obsessed with waist beads, and once he sees me in these, I might get pregnant again! I can’t go through that body journey right now.”

We laughed until tears rolled down our cheeks. She was dead serious though. She had finally nursed herself back to her “figure 12” and was not about to risk it. “These beads,” she said, “are dangerous in the wrong season.”

Now imagine that! A set of beads so powerful, so symbolic, that a woman fears their effect. Yet, in her voice, I could hear the flirtation, the longing, the quiet anticipation. She missed her husband. She wanted those beads. She just wasn’t ready to unleash them yet. And honestly? I couldn’t blame her.

That’s the thing about Tohma, it’s not just a gift; it’s a promise. It carries meaning, emotion, and memory. When a man buys waist beads for his woman, it’s his way of saying, “I see you.” It’s intimacy wrapped in culture, love expressed without words. It’s an act that connects to something ancient, the way African adornment has always been tied to identity, fertility, and sensuality.

Some women wear their Tohma beads immediately, others keep them for special moments, anniversaries, reunions, or times when love needs rekindling. In every case, there’s something quietly sacred about it. It’s not just jewelry; it’s a whisper of affection, a symbol of belonging. And when love buys you beads, it’s almost as if the beads themselves start holding memories for both of you.

So every time I pass by that Tohma pot in the studio, I smile. I imagine this woman’s reunion. The laughter, the rediscovery, the moment her husband finally sees her in those beads he chose for her four years ago. Maybe he’ll laugh. Maybe he’ll stare. Maybe he’ll just say, “Ah, finally.” Either way, it’ll be worth the wait.

Because Tohma is not rushed. It’s patient, playful, and full of meaning. It’s love’s way of saying, “I’m still here,” even when miles, time, or a post-baby belly try to get in the way.

So, do you have a tradition of wearing waist beads in your culture? What do they mean to you? Whether it’s love, legacy, or just your way of celebrating the woman you are? Remember: every bead tells a story. And sometimes, that story begins with love buying you beads.

Happy Beading.

Vera (Artist, Photographer & Bead Instructor at TALTOHMA)

References

Acheampong, L. (2020). Femininity and Symbolism: The Role of Adornment in African Womanhood. Journal of African Cultural Studies, 32(4), 512–526. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13696815.2020.1754953

Drewal, H. J. (2012). African Artistry: Beauty, Power, and Identity. The Smithsonian Institution. Available at: https://www.si.edu/object/siris_sil_913067

Okeke, N. (2022). Body, Culture and Sensuality: Understanding African Feminine Aesthetics. Journal of Gender and Culture, 28(1), 22–39. Available at: https://genderandculturejournal.org/okeke-2022